Structuring Ecosystems – An Applied Example

Especially within the last years we have seen high attention on network structures, organizational forms that question the traditional linear value chain and promote cross-industry collaboration, while each actor influences the other through his activities. The consultancy McKinsey estimates that by 2025 roughly $60 trillion in global production revenues could be distributed across industry borders while Accenture Strategy states that over 70 % of business leaders surveyed believe that business ecosystems will be the main change driver for business models within the next five years. Business ecosystems can be understood as dynamic communities of actors, which align around a shared goal to co-create and co-capture value (Burkhalter, 2019). Ecosystem role archetypes can be defined in relation to this shared goal of its members that materializes in the form of a particular service (Burkhalter, 2019). The user can be understood as the beneficiary of a particular service outcome. The provider is the supplier of the offerings needed to realize the service outcome, while the orchestrator acts as the coordinator aligning users and providers around that service outcome. Contributors complement the service outcome through their support offerings to either the user, the provider and/or the orchestrator. This simple structure provides a framework which can be used to increase transparency when it comes to these complex relationships and the underlying value co-creation mechanisms within the ecosystem.

Modern information and communication technology changed the mechanisms of relationships between companies and customers: the customer, for example, is by now deeply integrated in the value creation process. Therefore, value co-creation is an integral part of the concept of business ecosystems with “(…) manufacturers applying their knowledge and skills in the production and branding of the good, and customers applying their knowledge and skills in the use of it in the context of their own lives” (Vargo & Lusch, 2004, p. 146). Since all actors, including the user himself, within the ecosystem are a part of the value creation process, it is important to provide a common reference point. This reference point, or shared value purpose, materializes in a simple service, that adresses a primary need around which many complementing services will align in order to enrich the overall experience.

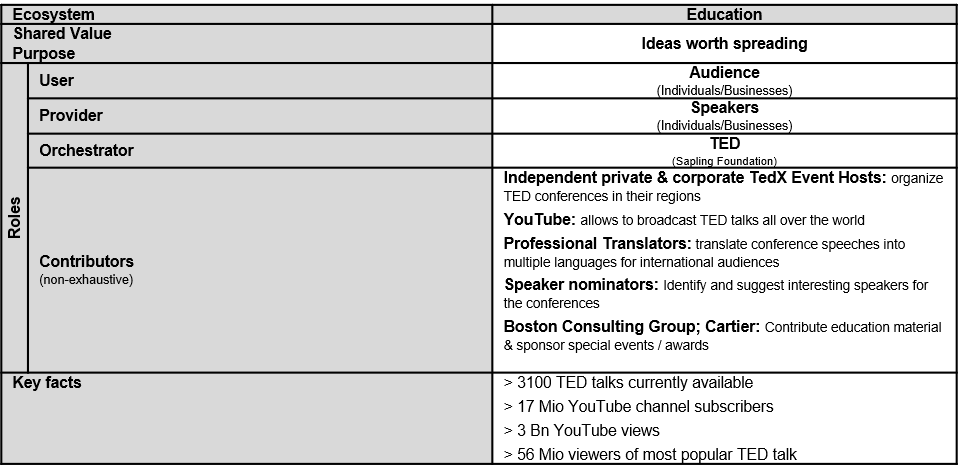

Many companies, such as Amazon, Alibaba, or Uber have understood this idea very well and designed their businesses in a way to address this perfectly. One fascinating and maybe less obvious example of how value co-creation in ecosystems works is offered by the Sapling Foundation, better known by their Technology, Entertainment and Design (TED) conferences. The organizers of this conference manage to bring the brightest minds together from fields like science, design, or innovation to present and spread their ideas. “Ideas worth spreading” was chosen as the overall slogan of this conference. However, this slogan acts as much more. It can be understood as the central reference point for various actors.

Firstly, TED provides a platform for individuals with exceptional ideas. They have the opportunity to present them, to get feedback and to spread them into the world. The ecosystem addresses their primary need to share their thoughts. This only works with an appropriate audience. While the speakers will present their ideas on a live conference, TED films and broadcasts these presentations and shares them with a global audience for free, thereby increasing the impact of such a presentation tremendously.

Secondly, TED provides a place for curious people, who are not satisfied with the first best answer they can get. While TED addresses this thirst for knowledge, the presentations are nonetheless entertaining to watch, therefore one might argue that curiosity alone might not capture everything those users see in TED. Again, we see individuals who pay prices in the large four digits to participate in a TED conference. However, while not everybody can take part in such a conference in person, there are more than 17 million Youtube subscribers of the TED channel with more than 3 billion views to date. This corresponds to a massive reach of TED talks.

Thirdly, there are multiple examples of contributors within this ecosystem of ideas. Lets look at TEDx, for example. “TEDx brings the spirit of TED’s mission of ideas worth spreading to local communities around the globe. TEDx events are organized by curious individuals who seek to discover ideas and spark conversations in their own community.” (TED, 2019). Individual and independent organizers are allowed to leverage the TED brand and to organize individual events by themselves – in order to spread even more great ideas. Youtube is another important actor in this ecosystem, as it broadcasts TED presentations all over the world. Translators, on the other hand, support the conferences by providing translations in multiple languages in order to reach an even broader audience. Many other partners like the Boston Consulting Group, Bose, BMWi, or Cartier also contribute to the events or awards thereby enriching the overall offering of this network.

Finally, in order for all these actors to come together efficiently, TED itself acts as orchestrator. They organize and promote the events, provide the technical infrastructure and host videos of the presentations – thereby supporting the impact of each and every party within the ecosystem. And this has to be emphasized: the orchestrator does not simply understand itself as the center of the ecosystem. Its main task is to support and promote each party so that they can get the most out of the ecosystem. Each party plays its own important role in this ecosystem: namely to provide, to promote, and to spread exceptional ideas. The table below summarizes the structure of the TED ecosystem.

Quellen:

Accenture Strategy. (2018). Cornerstone of future growth: Ecosystems. Von https://www.accenture.com/gb-en/insights/strategy/cornerstone-future-growth-ecosystems

Burkhalter, M. 2019. Allocentric Business Models – An Allocentric Business Model Ontology for the Orchestration of Value Co-Creation Using the Example of Financial Service Ecosystems, St. Gallen, Switzerland: Unpublished Dissertation, University of St. Gallen.

Iansiti, M., and Levien, R. 2004. “Strategy as Ecology,” Harvard Business Review (82:3), pp. 1-11.

Jacobides, M. G., Cennamo, C., and Gawer, A. 2018. “Towards a Theory of Ecosystems,” Strategic Management Journal (39:8), pp. 2255-2276 (https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2904).

McKinsey and Company. 2008. “Winning in Digital Ecosystems”, Digital McKinsey (https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/digital-mckinsey/our-insights/digital-mckinsey-insights/digital-mckinsey-insights-number-3).

Moore, J. 1993. “Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition,” Harvard Business Review (71), pp. 75-86.

Prahalad, C., & Ramaswamy, V. (2000). Co-opting Customer Competence. Harvard Business Review, 78, S. 79–90.

TED: Ideas worth spreading. Von https://www.ted.com/

Vargo, S.L., Lusch, R.F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing’, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 68, No. 1, pp.1–17.

Vargo, S. L., and Lusch, R. F. 2008. “Service-Dominant Logic: Continuing the Evolution,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science (36:1), pp. 1-10 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6).