Strategic Leadership in the Context of Digital Transformation (Part 1)

The primary goal of any company is to gain a sustainable competitive advantage in order to achieve a superior financial performance, also known as peer outperformance. This outperformance can be realized by optimizing existing cash flows or by tapping into new revenue streams. While in the past it was sufficient to improve a well-functioning business model through incremental innovation in an attempt to preserve its competitive advantage over the long term, an ever-changing environment with technological innovations and changing customer needs and expectations requires companies to constantly transform themselves and explore new business areas. For this reason, transformation in the context of digitalization is one of the major research topics at the CC Ecosystems. While we at the Competence Center focus primarily on transformation methods and capabilities, in this two-part series, I would like to focus on transformation governance, in particular the role of the board of directors and executive management in initiating and implementing a transformation. Part 1 focuses on the environmental changes that make a transformation necessary and outlines the measures to be introduced by the board of directors, while part 2 deals with the importance of different management systems for the long-term innovative capacity of a company. The theoretical concepts presented here are part of my master’s thesis “Strategic renewal in the form of digital transformation through business model innovation – a multi-layer governance perspective”.

The role of the board of directors in digital transformation

Transformation research has so far focused primarily on top management, middle management and local management in examining the contribution of different hierarchical levels to digital transformation. However, this focus is incomplete, especially for companies in Switzerland, as the board of directors is not only a controlling body under current law, but also the highest body responsible for the strategic management of the company. This requires the board of directors to have not only specialist knowledge, but increasingly also cognitive skills such as the perception and interpretation of increasingly different signals and sources of information. In order to perceive relevant developments in a dynamic environment, to understand their impact on one’s own company and to adapt resources and skills accordingly in order to maintain competitiveness in the long term, the board of directors is called upon to redefine its strategic role during the transformation process and to complement the more short-term oriented management of the executive.

Environment Scarcity

Ideally, the Board of Directors proactively initiates the strategic renewal before changes in market conditions cause it to do so, so that the company itself influences the direction in which the market will develop in the future. However, the reality is often that a company only recognizes the need for transformation when sales revenues are already declining and new competitors are positioning themselves in the market with innovative offerings. A change in the market environment, also known as “environment scarcity”, causes an imbalance between market requirements and the company’s resources and leads to organizational stress, for example in the form of declining sales or outflowing liquidity. This challenges the status quo and often triggers strategic renewal activities.

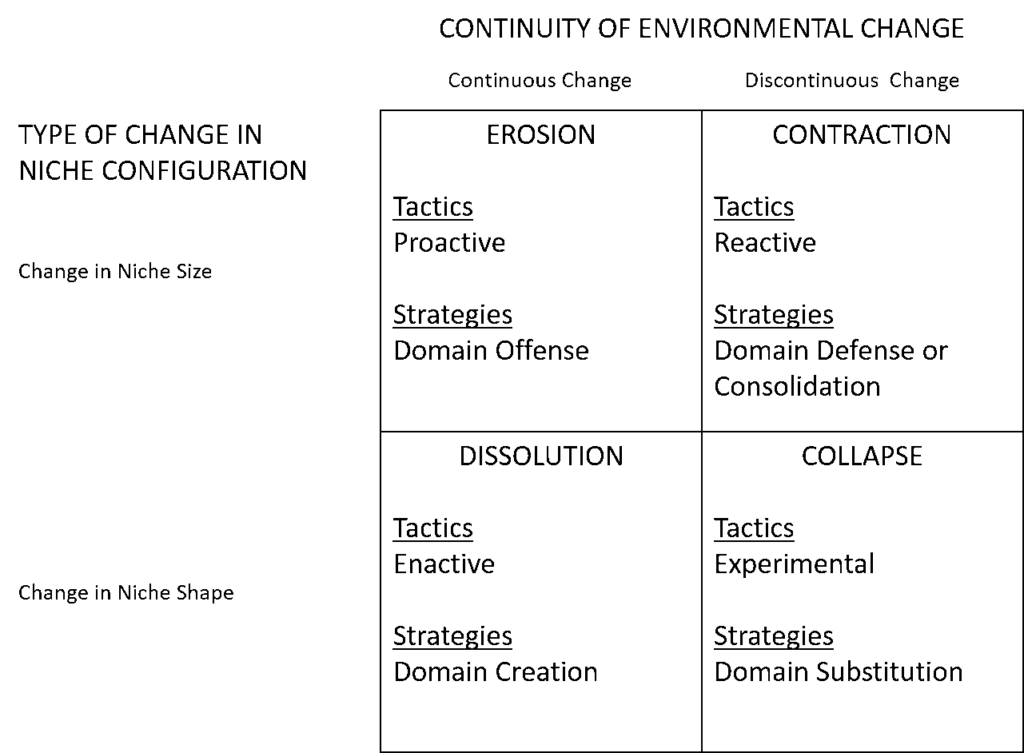

In scientific literature, the environment of a company is referred to as a niche. A niche is an economic space that is limited by the availability of resources to carry out a particular business activity, by the demand for the results of that activity, and by conditions such as government regulations, cultural influences and technological possibilities. Changes in a niche are divided into four groups, depending on how suddenly they occur and whether it is a change in the size or shape of the niche:

- Environmental erosion

- Environmental contraction

- Environmental dissolution

- Environmental collapse

Environmental erosion and environmental collapse are characterized by a change in the size of the niche. This change can be triggered both by a reduction in supply (e.g. due to a shortage of resources) and by a reduction in demand (e.g. due to recessions or an increase in taxes on certain products).

Environmental dissolution and environmental collapse, on the other hand, are characterized by the fact that other products are increasingly demanded by the same consumers and the niche itself is changing. Such changes in demand can be triggered by technological developments that enable new, better products and services, changes in government regulations that previously prevented certain services from being offered, or changing social preferences. An example of the latter is the currently discernible trend towards sustainability.

The second dimension used to categorize environmental changes, besides the type of change (size vs. shape), is the speed of change. For example, the sudden disappearance of a niche requires management to take different measures from those required for a gradual decline, which provides sufficient time to identify the danger and initiate countermeasures.

Figure 1 shows the typology of environmental changes by type and speed of change, together with recommended responses and strategies for the respective situation.

A slow decline of the niche, which can be predicted by management on the basis of long-term developments, as in the case of environmental erosion, allows early, proactive adaptation to new circumstances. Depending on the cause of the shrinking of the niche (erosion due to scarcity of resources or declining demand), the production input could, for example, be adjusted, new product lines developed, new markets entered or the penetration of the existing market increased. As these measures are primarily aimed at expanding business with existing products or existing customers against environmental trends, they are summarized under the term ” domain offense”.

If the environment changes suddenly, as in the case of environmental contraction, emergency measures are first required to guide the organization through the crisis. Such measures include focusing on the core business and cost savings to bridge the time until a temporary shortage of resources is overcome or until the existence of the company is secured to such an extent that the management has sufficient freedom to develop a new strategy. Due to the concentration on defending the core business, this strategy is also called “domain defense” or “domain consolidation”.

Environmental dissolution requires a similarly proactive approach as environmental erosion, but the development of new services is no longer optional as the acceptance of existing services is increasingly declining. New value propositions must be found and new resources developed to find a new area of activity for the organization. This is why the strategy required here is called ” domain creation “.

Finally, environmental collapse poses the greatest challenge for companies, as the company is quickly deprived of its raison d’être, for example through the success of a disruptive innovation that was initially not interesting for its own customers due to poor performance and was therefore not considered a threat by management. In such a situation, there is no time for the long-term development of new areas of activity. Instead, the aim is to convert the company’s activities as quickly as possible to a new value proposition in a new market through experimentation and the development of new resources. This can be done, for example, by acquiring new technologies or companies within the new domain.

Regardless of what triggered the digital transformation: every transformation also means innovation for the transforming company. This innovation can be developed internally or integrated into the company through acquisitions from outside. Which of these options is selected depends, on the one hand, on the expertise available within the company and, on the other hand, on the prevailing management system, i.e. on the type of guidelines used by the board of directors to set targets for top management and against which it evaluates performance. There are basically two options available to the Board of Directors: strategic control or financial control. The advantages and disadvantages of these types of control and which style is preferable in which circumstances will be explained next week in the second part of this article.

Sources

Cameron, K., & Zammuto, R. (1983). Matching managerial strategies to conditions of decline. Human Resource Management, 22(4), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930220405

Floyd, S. W., & Lane, P. I. (2000). STRATEGIZING THROUGHOUT THE ORGANIZATION: MANAGING ROLE CONFLICT IN STRATEGIC RENEWAL. Academy of Management Review, 25.

Gassmann, O., Frankenberger, K., & Csik, M. (2014). The business model navigator: 55 models that will revolutionise your business. Harlow, England ; New York: Pearson Education Limited.

Gupta, A. K. (1987). SBU STRATEGIES, CORPORATE-SBU RELATIONS, AND SBU EFFECTIVENESS IN STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION. 25.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Ireland, R. D. (1994). A Mid-Range Theory of the Interactive Effects of International and Product Diversification on Innovation and Performance. Journal of Management, 20(2), 297–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639402000203

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Moesel, D. D. (1996). THE MARKET FOR CORPORATE CONTROL AND FIRM INNOVATION. Academy of Management Journal, 37.